welcome to my world . . .

the enchanting eloquence and creativity of an Iraqi woman

To Be a Refugee

Means you walk with a mute dignity

And because the touch has a memory,

you can no longer make another one,

No sea can reveal to you the joy of its

flowing

and its every wave is shackled with corpses

and identities

of drowned people, no land will welcome

your shy steps.

To be a refugee

You have to wear a stainless smile in front

of their serrated gaze.

You have to get rid of your ancient history,

Your mother's prayer for your safety, which

no longer works

The wisdom of your ancestors, which they

left to you

before they disappeared into their graves.

To be like me,

You have to peel off your skin, pull out

your tongue

in order to get along with the crowds that are

waiting

for any slight movement from you to finish

you off.

Above you have to be very sane in the

streets that know

nothing but where madness erupts,

And like swimming in a river of blood,

you will remain stained until the end.

A MEMOIR

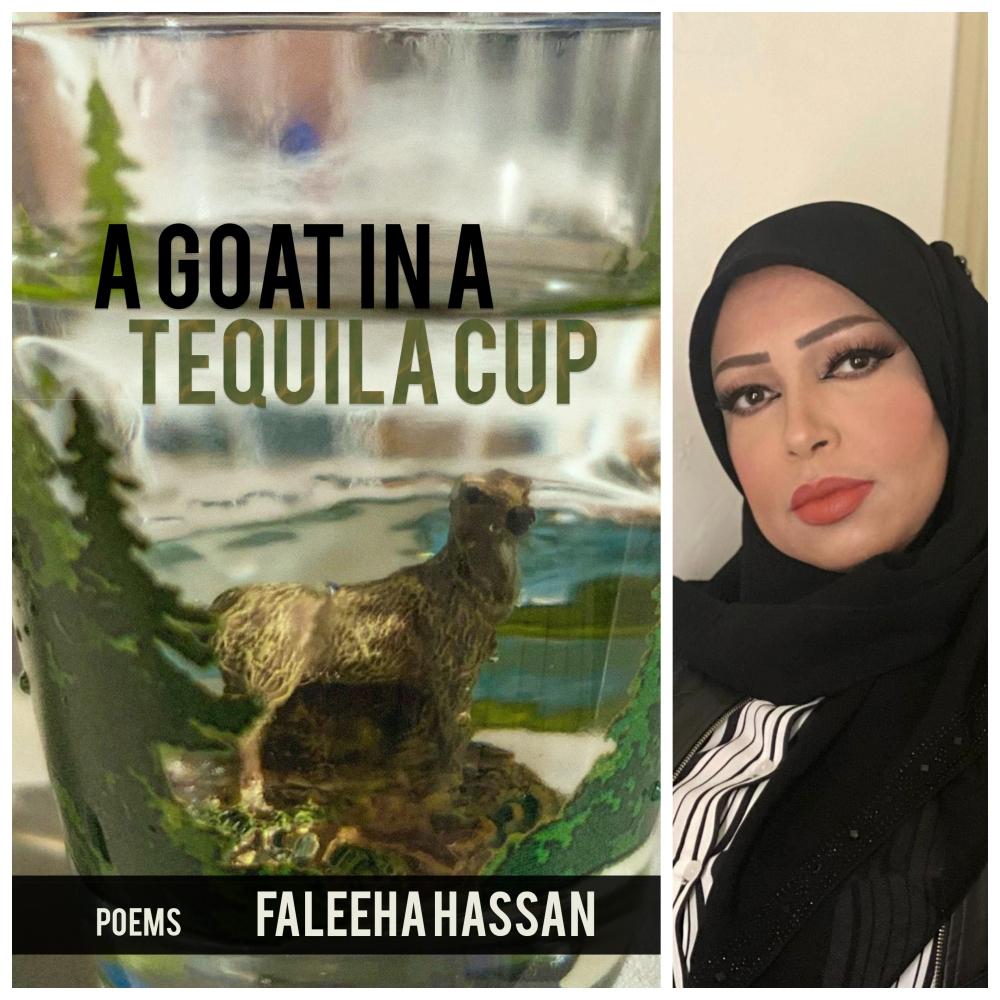

by Faleeha Hassan ; translated by William Hutchins ‧ RELEASE DATE: Aug. 1, 2022

An Iraqi poet depicts her wrenching childhood and coming-of-age under her country’s series of debilitating wars.

Growing up in the small town of Najaf, Hassan was the eldest in a growing middle-class family—her father had to work two jobs as a clerk and a cook—that moved often to find better housing and educational opportunities for her and her siblings. School was her refuge, and despite the increasingly tumultuous political events in Iraq, she excelled. By 1980, however, everything changed with Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Iran. “This year and the following ones tattooed all Iraqis with loss and death,” writes Hassan. Though Hussein and his advisers boasted that it would be a quick conquest, it became an eight-year slog that destroyed the country’s economy and caused the senseless deaths of countless Iraqis—all while Hussein ordered the construction of more than 100 lavish palaces. “Ordinary people,” writes the author, “experienced brutal lives as they endured the scourge of abject, relentless, crushing poverty, having been deserted by their government, which had inflicted these woes upon them.” In a vividly detailed narrative, the author is always candid, unafraid to express her feelings. From 1980, she writes, “I was obsessed by a feeling of revulsion—as if a large snake had swallowed me.” School disruptions, food scarcity, the sudden disappearance of friends and family, air sirens, explosions, and government surveillance—all marked her formative years. Fortunately, her father supported her education, and she became an accomplished teacher and then a published poet, the first woman in her town to achieve such a feat. She reluctantly gave in to her family’s wishes and married a man she did not know. The union was disastrous, and Hassan endured death threats by a virulently chauvinistic society that pursued her relentlessly into exile. Throughout, Hassan renders her harrowing experiences in an authentic, heartfelt manner, offering important testimony of personal and national courage.

A beautifully wrought memoir from a pioneering Iraqi author.

https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/faleeha-hassan/war-and-me-memoir/

My Life as a Refugee

Faleeha Hassan

~ * ~

Once my name appeared on a death list published in a number of newspapers and on some websites, I decided to flee Iraq and went first to the Turkish city of Eskişehir—on the advice of an Iraqi friend who lived there. I only lived there a month, however, because I had a hard time adjusting to that city, especially to the high cost of living.

So I moved to Afyonkarahisar, where apartments were available for rent at a reasonable rate and where many Iraqi families lived. This is a mountain town that has harsh winters. By three p.m. the temperature may descend below zero degrees centigrade. Then vendors’ fruits and vegetables freeze in the markets and they are forced to toss them out.

During the year and a half, approximately, that I stayed in Turkey, I did not meet a single Turk who spoke English or Arabic. In Afyon an Iraqi child of Turkmen ancestry spoke fluent Turkish, and we hired her for a modest fee to interpret for us whenever we went to a government bureau.

It was not easy to enroll my children in school. The school principal refused to admit them on the grounds that they did not know Turkish. So I was forced to appeal to the superintendent of education. When he asked why I wanted to send my children to school even though they did not know Turkish, I replied, “To keep them warm!”

This actually was my reason for insisting they be admitted to school, where they would be warm—unlike our apartment, which was unbearably cold. In the neighborhood where we lived residences used coal-fired space heaters. I bought one but was never able to get it to operate properly, even after repeated tries. Coal smoke would fill the entire apartment; so whenever I lit it, we almost suffocated. Therefore enrolling my children in school was my only way to protect them from the cold. At night we wore heavy clothes like wool socks, caps, and leggings--and occasionally mittens. Then we slept huddled together beneath four blankets.

Turkey is known for its local open-air markets. These are held daily but in different areas. Where we lived the market was held each Friday morning in the valley. The other market, on Sunday, was held on the mountain. For the most part, people who lived in this city frequented the Sunday market, because everyone could walk to it.

To reach other markets a person had to ride a bus, and the Turks did not like to ride buses in the winter. All the same, shopping on Sunday was rather like mountain climbing. One day when I shopped while my children were in school my foot slipped. Then I fell a long way down the slope. People came to help me and carried me home on a thick wooden stretcher they used in cases like mine. I could not get about for two weeks. When my pain became more bearable, I sought treatment in a public clinic in our area.

When I healed some more, my son Ahmad caught German measles from some Turkish pupils in his class. I took him to a doctor, who wrote a prescription for him. The medication cost 80 Turkish lira (about 80 US dollars at the time). This was a horrific sum, compared to the cost of food and rent. Fresh fish, for example, might cost 5 liras, and the monthly rent for our apartment was only 250 lira. All the same, I had to purchase this medicine for my son, even though that meant I lived on bread and water for a time. What else could I do when I was unemployed?

After I purchased this medicine, an Iraqi woman who lived in the neighborhood told me there was a clinic to which people donated unused medicine, including bottles they had opened. The clinic distributed these to people who needed them. I did not go there for fear those medicines were past their expiration date or unfit for use for some other reason.

Fearful, anxious, and lonely, I realized that my psychological condition was deteriorating. I also began to suffer from chronic insomnia; I had lost the ability to sleep at night. If I did fall asleep, I would wake a couple of hours later after having nightmares and terrifying dreams about men racing after me and trying to slay me or blow up the room around me. So I woke up frightened and soaked with sweat.

I asked the agency in charge of Iraqi refugees in my city whether there was a psychiatrist who would treat me. A month later, an employee contacted me to tell me a woman psychiatrist could see me the next Friday at the bureau. I went and found her waiting for me with an Iraqi woman, who translated for me. The Turkish physician asked me some medical questions, and I told her candidly about my daily travails. She simply advised me to mix with other people, read the Qur’an, and wear a blue headscarf.

What could I do but thank her and leave? I wondered, though, whether this physician had ever treated a genuinely ill patient. That was the last time in Turkey or America I thought of consulting a psychiatrist. I adjusted to the fact that I have nightmares and terrifying dreams.

I did follow the physician’s suggestion to try to socialize more and started taking my children to a large public park where people from various neighborhoods congregated. They chatted while their children played a lot of different games. Because Friday was a school and government holiday, I began to take my children to this park each Friday morning. Every time Turks sitting there caught sight of us, though, they would laugh, mocking me and my kids because our brown complexion was darker than theirs. So I was forced to sit in a far corner of the park, away from the adults and near where the children played.

Our landlady had divided a large house into four small apartments. She lived in the best one, which had a sunny exposure. The other units were inhabited by three Iraqi families. This Turkish landlady was very domineering. She had even accused her husband of theft and sent him to prison. So she lived there with only her teenage daughter.

She owned a huge dog that she kept on a chain by the door. She also traveled to Istanbul frequently, going there more than four times a month. Whenever she was out of town, she entrusted care of her dog to my Iraqi neighbor, who lived on the ground floor with his wife. He fed the dog, made sure it had water, and cleaned up after it. In the absence of its mistress, however, this dog was vicious during the day and would not stop barking all night long. Its caretaker was frequently bitten, but when the dog’s owner heard what her dog had done, she would laugh and boast about her beast’s heroism.

Each month, just as soon as I paid her the rent, this landlady would ask me for more money—a loan she would never repay. When I refused, she would become angry and speak so loudly that I could not understand her.

As if that wasn’t enough, she grabbed our lower water and electricity bills and left us her higher bills, because she felt certain the lower ones were intended for her. We awoke one morning to the sound of heavy pickaxes. When I opened the door, I was surprised to see three workmen outside with the landlady. She had hired them to demolish the steps to our residence. Infuriated, I contacted the police and phoned the child interpreter and her father. Then I asked the girl to explain my plight to the policemen. They took no action against the woman, however, because she said she was remodeling the apartment for a visit from her mother during the Eid celebration. She also claimed that the new steps would be completed by the next morning. They were not, and we were confined to our quarters for three days, unable to clamber down.

During those days I would write out a shopping list for an Iraqi woman neighbor. I placed it and some money in a basket that I lowered to her with a rope. Then she bought whatever we needed and brought our provisions to us when she returned home that evening.

My dreadful, frightening experiences and my insomnia motivated me to try to write a novel. So I wrote a novella a hundred pages long and called it I Hate My City. (A partial English translation is posted online at: http://www.wordgathering.com/issue33/fiction/hassan.html). One day I was on Facebook, chatting with an ingenious friend, and told her about my manuscript. When I asked about the possibility of publishing it, she suggested I send her the file and offered to try to submit it to an Iraqi publishing house in Irbil, in northern Iraq. So I did. Soon afterwards she sent me an email to tell me that the publisher had agreed to print and distribute the novel. As soon as it was edited, he would send it to the printer. Three months later I learned from my friend that the novel had been released and would be displayed at an international fair in Irbil. She also mailed five copies of the novel to me in Turkey.

I never felt comfortable in Turkey, because it was not a safe distance from my enemies in Iraq. So I never felt secure there and was haunted by fear and anxiety. Then I started asking fellow Iraqis in Turkey about the possibility of leaving for a distant country. They told me that I needed to register with the UN in Ankara.

I did take my children by bus to Ankara--a trip that lasted many hours. When we reached the UN office we found lots of people waiting outside the door, trying to enter. After waiting a long time we were finally admitted to a lobby that was crowded with a large number of people from various parts of the globe.

Once we had registered, they asked why we were applying for humanitarian refugee status. Then I recounted the history of my calamities as a refugee. They said they would telephone us to conduct a second interview. That did occur and was followed by a third one. Eventually we were assigned to America and an interview was arranged with a representative of the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program.

The Americans arranged a three-day workshop for us, and during it we had physical exams to check to make sure we had no contagious or chronic diseases. Because I had no family or relatives in America, a representative of a Roman Catholic charity in New Jersey contacted me and told me that my children and I would be received by them in New Jersey.

One rainy day in August we reached America. At the Philadelphia Airport we found two Americans from the charity and an Iraqi woman translator waiting for us. They took us to the charity’s headquarters in Camden where Mrs. Cathy, the head of organization, welcomed us. She had rented an apartment for us in Gloucester, paying the rent in advance for three months. They also provided us with food vouchers.

Some of our new neighbors, though, did not like having Arab Muslims near them, and a woman who lived on the ground floor started harassing us every day. She would turn up the volume of her TV till it was really loud and leave it like that all night long. At six in the morning she would play the childish prank of ringing our doorbell. She would drop metal weights her husband used for physical training really hard on the floor, making our whole apartment shake. After I discovered her taking photos of my children with her mobile phone, I became so frightened and furious that I complained to the woman who managed the apartment complex. She wasn’t able to stop the woman’s harassment, and I contacted the police. My tormentor told the officer that her husband had been deployed to fight in Iraq and that since we were Iraqis we should be killed. Then the policeman merely smiled and did not write her up. So I was obliged to move to another apartment far away from her.

Now I live somewhere else, but even so it isn’t easy being a Muslim woman who wears a headscarf in America. Many people, knowing nothing about me, assume I’m a terrorist.

The limit of their knowledge about Islam is the distorted picture some media outlets continue to broadcast every day. My one request is that people should not hate other people simply because they differ in appearance, complexion, race, or creed. We all share a common humanity; that’s the important thing.

Translated by William M. Hutchins

Kawkab Hamza كوكب حمزة ـ أغنية بساتين البنفسج.mp3